World War One - A Revolution in Military Communications

This article first appeared in the Telecommunications Heritage Journal, Issue Number 88, Autumn 2014 and is reproduced with the permission of the Telecommunications Heritage Group.

During 2014 we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the start of the first World War. A war which revolutionised military communications and ultimately led to the formation of the British Army’s Royal Corps of Signals, commonly referred to as Royal Signals, on the 28th June 1920. Prior to this the Royal Engineers (RE) Signal Service provided the British Army with military communications, having been formed in 1908 from previous RE Telegraph Battalions. When war broke out in 1914 there were fewer than 6,000 men in the RE Signal Service. By the end of the war there were 70,000[1].

The Signal Service at the start of the war was primarily a Telegraph Service however by the end of the war the telephone was the main means of communication on the Western Front. Wireless was playing an increasingly important role too, particularly for communicating with the aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps which, in 1918 became the Royal Air Force.

Members of the Royal Engineers Signal Service wore the Royal Engineers cap badge along with RE shoulder titles which were worn with Signal Service titles. Figure 1 shows the regular and territorial badges. It is also known to have been worn with the RE and Signal Service joined together to form a single badge[2].

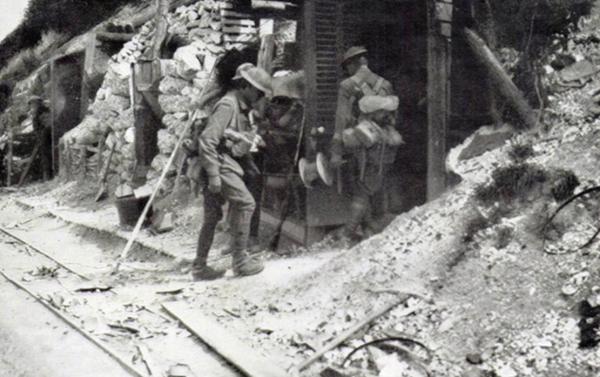

The Signal Service was trained and equipped to operate in a mobile role, moving forward with an advancing army, laying telegraph lines from cable wagons, often under enemy fire. The deadlock which resulted in years of trench warfare changed the work of the Signal Service and placed significant demands on its resources. In 1914 a signal office at a typical Corps HQ would consider 100 messages a day to be busy, by 1918 the average daily number of messages had reached 4,500[1].

A wide range of techniques were used to provide military communications, these ranged from despatch riders, increasingly using motorcycles rather than horses to traditional carrier pigeons, a large number of homing pigeons were trained and used on the front line to send messages back to headquarters. Telegraphy was very well understood and techniques for deploying cables were well practiced however the telephone offered a significant improvement over all of these methods of communication. Interestingly the Army Pigeon Service was transferred to the newly formed Royal Signals after the war and was not disbanded until 1946.

Some military telephones were available at the start of the war, these were manufactured by Ericsson who had been supplying the British Army since the Boer war of 1899 - 1902, unfortunately there was nowhere near the quantity of instruments required to meet demand. During the early days of the war, civilian telephones were deployed to meet the immediate needs for battlefield communications, however these instruments were not designed for the harsh environment in which they operated. Many of these civilian telephones were replaced, as soon as possible, with specially designed instruments such as field magneto telephones and buzzer systems for use with Morse code.

The use of telephones on the battlefield presented new security risks as the enemy could easily intercept the communications, thousands of casualties resulted from intercepted telephone conversations until Army staff started to speak in code to minimise this risk. Engineers worked to improve the design of telephone cables to prevent the leakage of signals while Captain (later Major General) A C Fuller invented the Fullerphone which made the Morse code buzzer phone secure, this entered service in 1916 and was still in use by the British Army at the start of the Second World War in 1939.

I have a wonderful reference book in my collection titled: Instructions in Army Telegraphy and Telephony, published in 1914. This book provides an insight into the technology and operating practices of the day with chapters covering elementary theory and batteries, galvanometers and simple telegraph circuits, the high-speed Wheatstone automatic system through to telephone sets and the telephone exchange. Those wanting further information are directed to “Telegraphy” (by T E Herbert, 1906) and “Telephone Handbook” (by Poole, 1906).

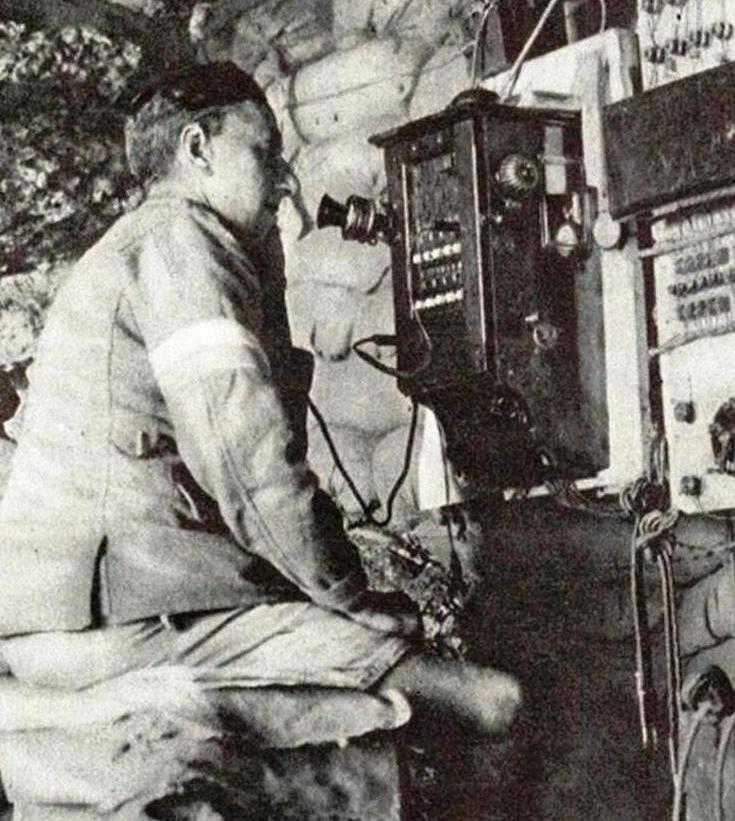

The Illustrated War News published the photograph shown in figure 3 on the 1st November 1916, Titled; The Telephone in War: A Salonika Exchange.

Anglo-French forces began landing at the Greek port of Salonika (now Thessaloniki) on the 5th October 1915 and quickly established a telephone network to support military planning and operations. Lord Northcliffe, after visiting the front described the Army telephone system as unique. Every Officer he wrote, or head of department of importance in the British zone has a telephone at his hand. The Morning Post also reported on the efficiency of the British Army’s telephone service, stating that You go into a stable (at GHQ) and see a switchboard which connects every command along the line in addition to those which go to London or Paris. You can call up the Ypres salient or the base in less time than it takes to get . . . to Gerrard.

As with all military actions; be they small scale or major wars, a comprehensive analysis of the events and outcomes is completed afterwards to learn lessons and improve future capabilities. Good communication helps to win battles, this has always been the case however the scale of communications systems in World War One was greater than ever before, we were entering an era of rapid developments in fixed and wireless telecommunications and the military had to be at the forefront of these developments. The result was the formation of the Royal Signals, a Corps which provides the British Army with a wide range of fixed and mobile communications solutions to meet the diverse nature of military operations around the globe. The Royal Signals museum is located at Blandford Camp in Dorset where you can follow the story of military communications from the days of the Shutter Telegraph through the events of World War One as described in this article, through to the present day.

The need for the message to get through quickly and accurately is essential, this is fundamental to military communications and as such the Royal Signals Corps motto is ‘Certa Cito’ which translates to Swift and Sure.

The Royal Signals museum website can be found at: royalsignalsmuseum

Bibliography

[1] Call to Arms – A History of Military Communications from the Crimean War to the Present Day

[2] Headdress, Badges and Embellishments of the Royal Corps of Signals

Additional Reading

Work of RE in the European War, 1914 – 19: The Signal Service (France)

The Royal Corps of Signals – Unit Histories of the Corps (1920 – 2001) and its Antecedents

Innovating in Combat: telecommunications and intellectual property in the First World War

Presentation

A version of this article entitled: The impact of World War One on Military Communications was presented by Professor Sutton during the AGM of the Telecommunications Heritage Group held on Saturday 8th November 2014 at the Science Museum in London.

Follow on social media .....